What projects do you usually think of when you hear “contributing to open source”? React? Rails? Kubernetes? TypeScript? Yes, those are open source projects but not all open source projects have to be at this as large as these. Most projects you find on GitHub are open source (depending on their license). I wrote this post to dispel the idea that many developers I’ve met (including myself!) had which is that contributing to open source is hard. This notion that many of us have is usually a result of thinking that contributing to open source is helping build new features or fixing bugs in these large scale projects. Start small and work your way up.

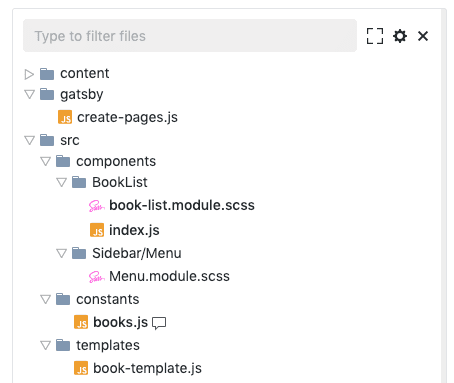

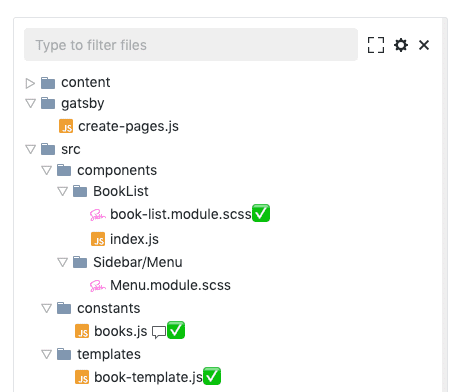

My first open source contribution was to a project called Better Pull Request for GitHub. It’s a chrome extension that adds a file tree to GitHub pull requests to improve the code review experience. I was using it for a few weeks and kept running into the same issue over and over: when viewing the file tree it was hard to tell which files were already viewed and which weren’t.

Files that hadn’t been viewed yet were bolded but the font weights weren’t distinct enough to notice at a quick glance. The extension already had a feature where it added a message bubble next to the files that had comments in them. I wanted a similar icon experience for viewed files. Instead of waiting for this feature to be built I decided to take a stab at it myself.

Building my first feature

I always feel overwhelmed when I have to browse other peoples projects on GitHub. GitHub’s directory structure UI to navigate a project’s codebase is awful and since I didn’t write any of the code I didn’t know where to look for things. I took a step back and thought: if I was at work and this was a codebase I have never touched, how would I go about debugging an issue? So I opened the Chrome dev tools and inspected the DOM tree.

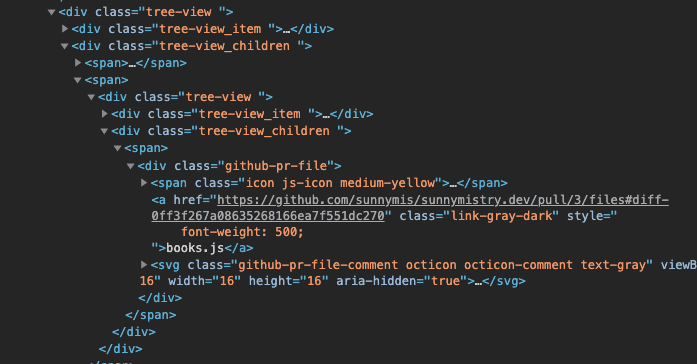

There was a class named github-pr-file that was near where I wanted to put an icon so I searched the codebase for that class.

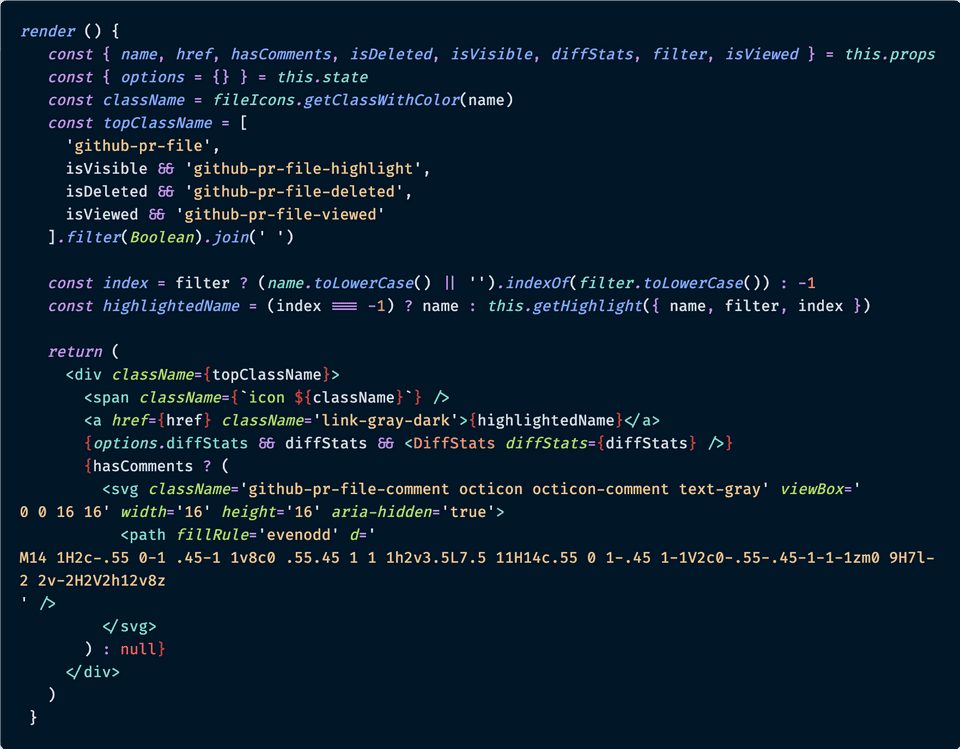

The search brought me to a render() function:

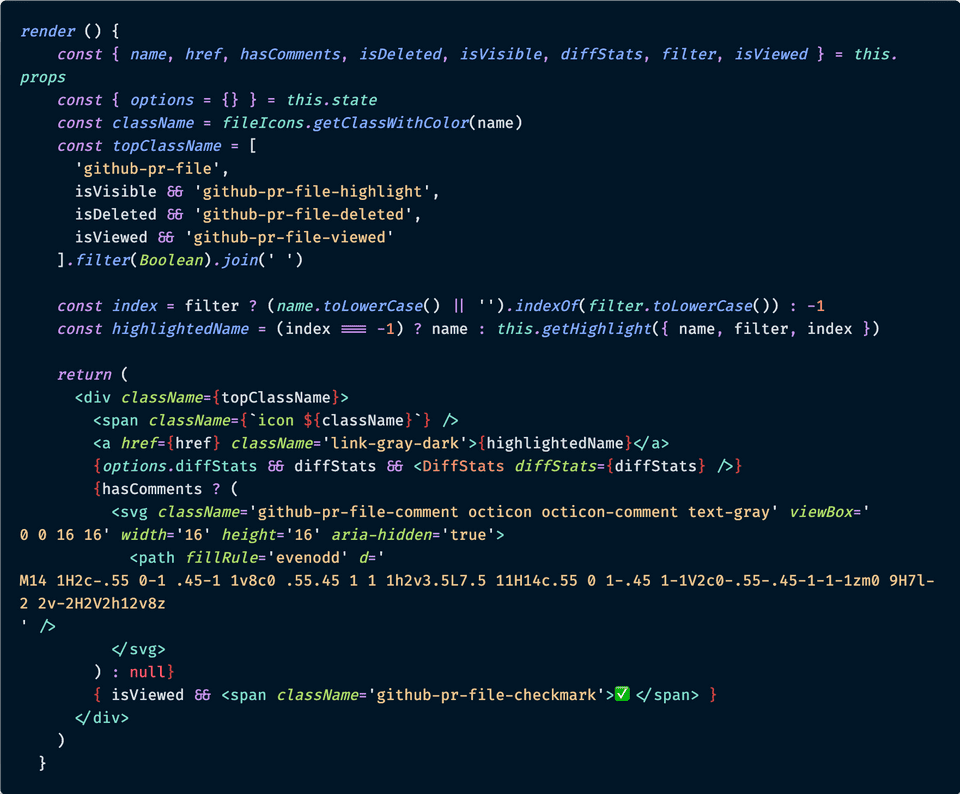

Reading the code I noticed an isViewed and hasComments boolean.

The hasComments conditionally renders an SVG so it seemed logical to apply a similar logic for isViewed to include

an SVG. I didn’t have an SVG at the time so I just rendered an emoji to see if it’ll work.

I ran the extension locally and it worked! Emojis were showing up next to viewed files.

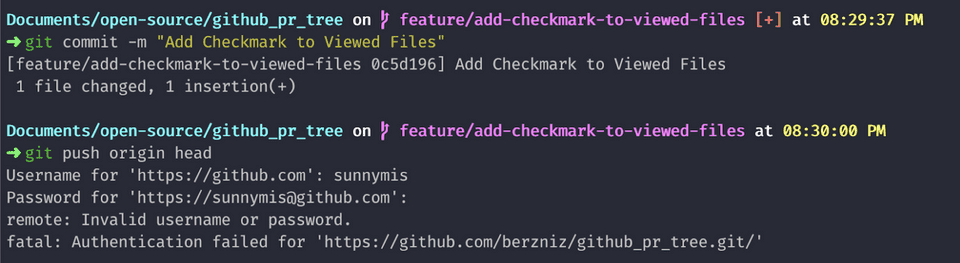

Everything was working as expected so I staged my changes, committed and pushed up to GitHub like I normally do. But then I was presented with the following error:

Forking Workflow

So what the fork just happened? Since I don’t have write access to the repo for Better Pull Requests I wasn’t able to push up changes on my feature branch. The solution to this problem, as you might have already guessed, is forking.

Let’s look at the forking workflow:

1. Fork the official repository 🍴

Forking a repo is as easy as clicking the Fork button at the top right of the GitHub project page. What does it mean to fork a repo?

The repository you want to contribute to is stored on GitHub’s servers. Forking creates a copy of the repo on GitHub’s servers and it

gives you write access to that copy. The forked repo functions just like any of your personal repositories.

2. Cloning the fork 🍴🍴

Cloning the forked repo downloads it to your computer. You can create and edit files, push up changes, or anything else you would normally do using git.

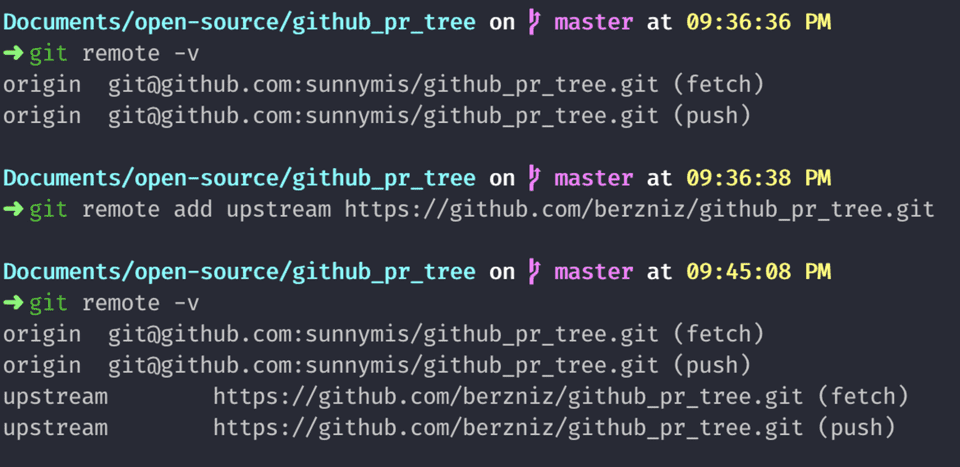

git clone git@github.com:sunnymis/github_pr_tree.git3. Setting upstreams 🌊

You might be thinking if you copied another repository on GitHub’s servers and downloaded that copy onto your computer then this new repo is completely separate from the original project. How do you stay up to date with the latest changes to the project? Your feature might take a week to complete and over the course of that week people all over the world might be making updates to the project.

The solution here is to set upstreams. An upstream is just a fancy word to denote the original repository your code is forked from.

GitHub lets us define multiple remotes which are URLs to repositories stored on GitHub’s servers. By default your only remote is

the project you cloned. We can create any number of remotes. By convention we create a remote named upstream to point to the original

project.

We can then pull in any changes that have been merged:

git pull upstream master4. Code! 💻

Once all of this setup is complete we can begin coding! You can create a new branch, make updates, push branches up, etc. When your code is pushed up you can create a pull request to merge your fork into the original repository.

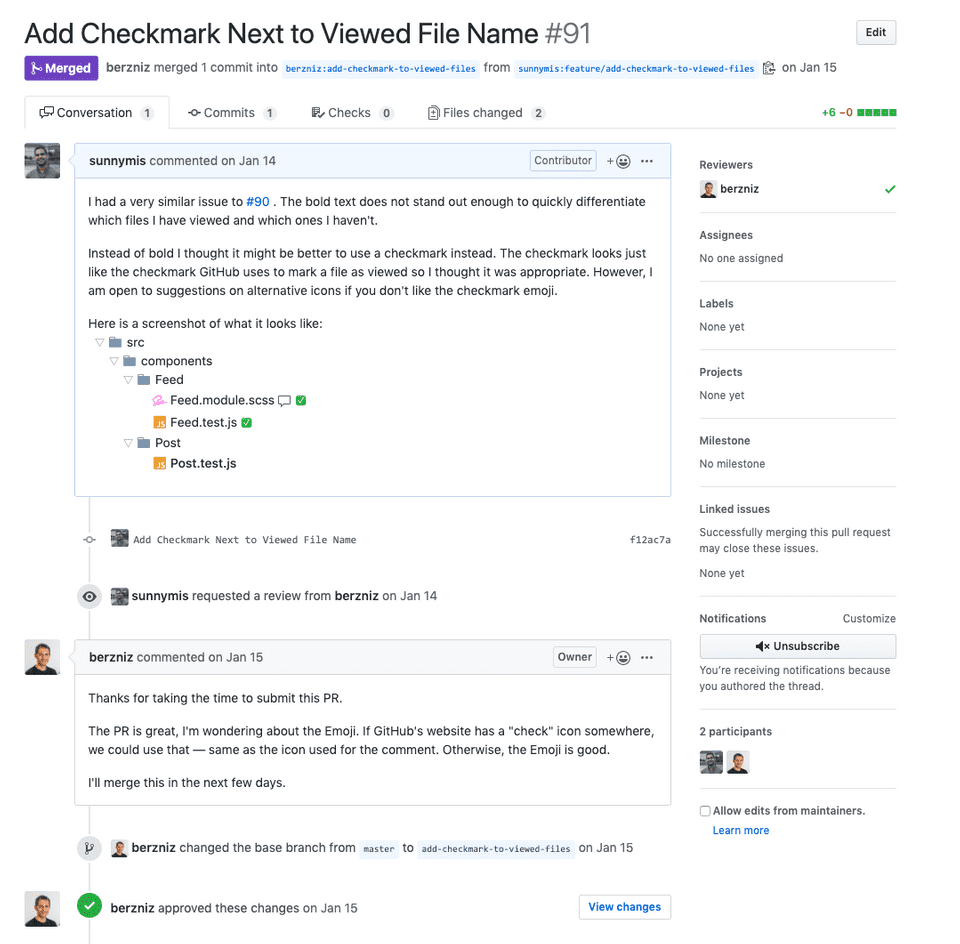

5. Create a Pull Request 📃

A pull request can be created from the GitHub UI when you push your branch up. A good pull request usually has a detailed description outlining the solution and why it needed to be made. It might also include any relevant screenshots or links to resources. If there are any outstanding issues on the GitHub project this is a good place to link those issues. Project maintainers will review your pull request and the code changes that it contains.

6. Repeat (maybe) 🔁

If you’re lucky your code gets accepted and is merged into the original repo. But, as with most code reviews, changes might be requested and you may have to revisit your solution or tweak some things.

7. Celebrate 🙌

Your code gets merged in and you can enjoy the incredibly rewarding feeling of contributing to an open source project.

Forking Workflow Benefits

Forking repos, cloning them, and setting up upstreams seems like a lot of work. Why do we need to do all of this work? There are three benefits I see with this set up:

- Contributions can be made without having everyone push to a single central repository

- Gives project maintainers more control over their repos

- Not every developer needs write access to every projects

Contributing Tips

Before you jump in to fixing a bug or building a new feature it’s important to take a look at how people are contributing. Every project is different and their processes will differ.

- Read the

CONTRIBUTING.mdfile before getting started. Here’s the Rails contributing guide - Read the

LICENSE.mdfile. Licenses determine how software can be modified, shared, used etc. Here’s the React license - You may have to sign a Contributor License Agreement (CLA) before merging your code in

- Be patient and open to feedback. This is probably the most important. People work on open source projects through the kindness of their heart and don’t usually get paid for it. This isn’t their full time job. Sometimes it might take a while for someone to reply and if they do they might not agree with what you built. Be mindful of that and be open to receiving feedback.

Contributions can be small

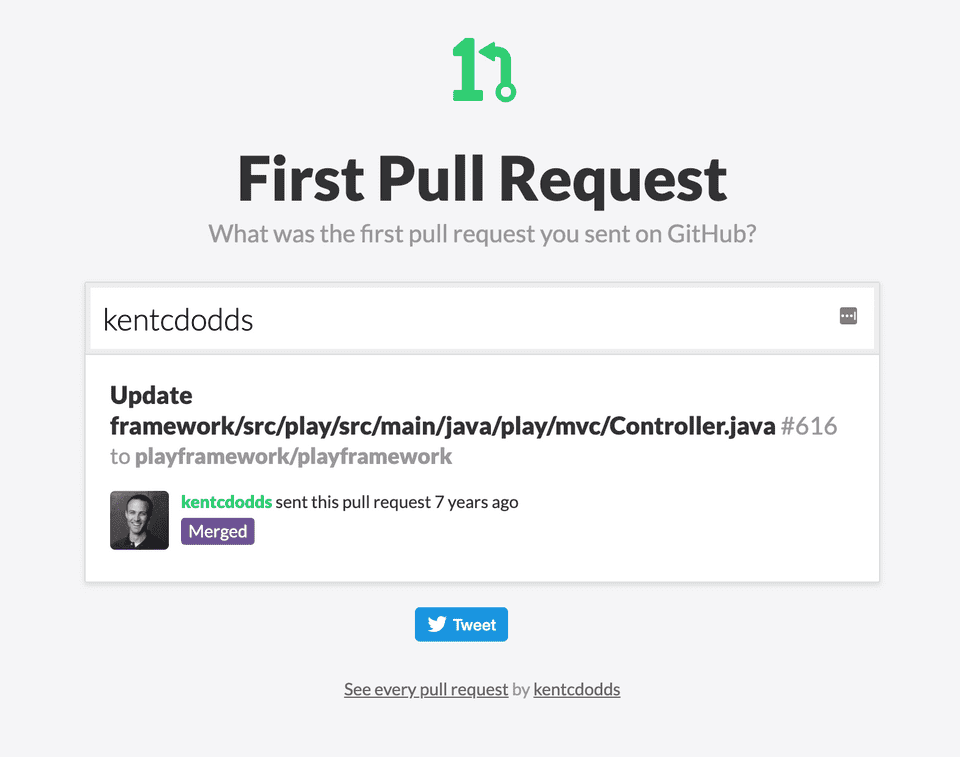

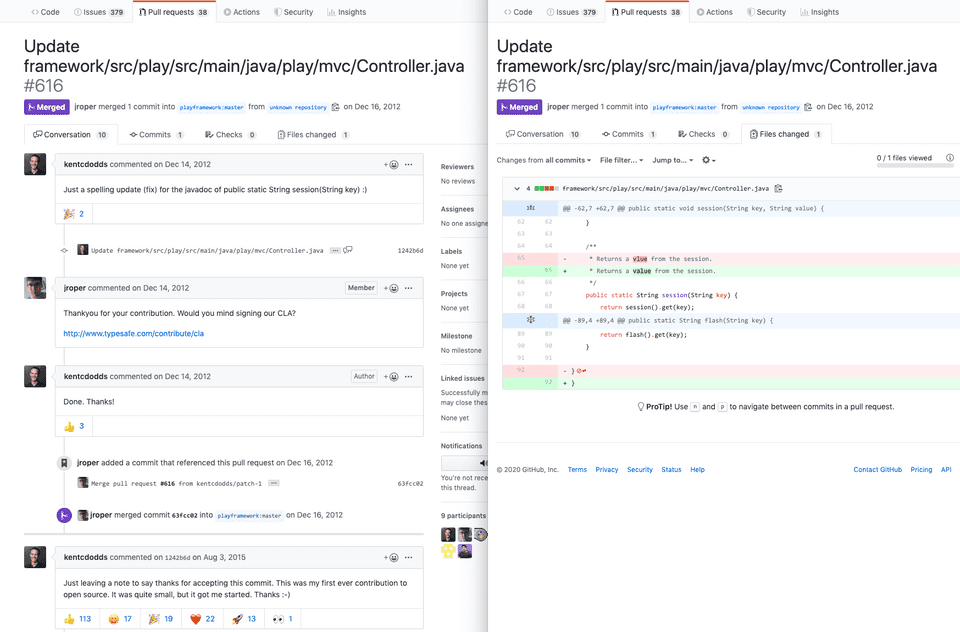

The site firstpr.me shows you the first public pull request for a given GitHub user. A great example of a very active open source contributor who began with small contributions is Kent C. Dodds. His first PR was fixing a typo in a javadoc. This is a much smaller pull request than the one I made.

Finding projects

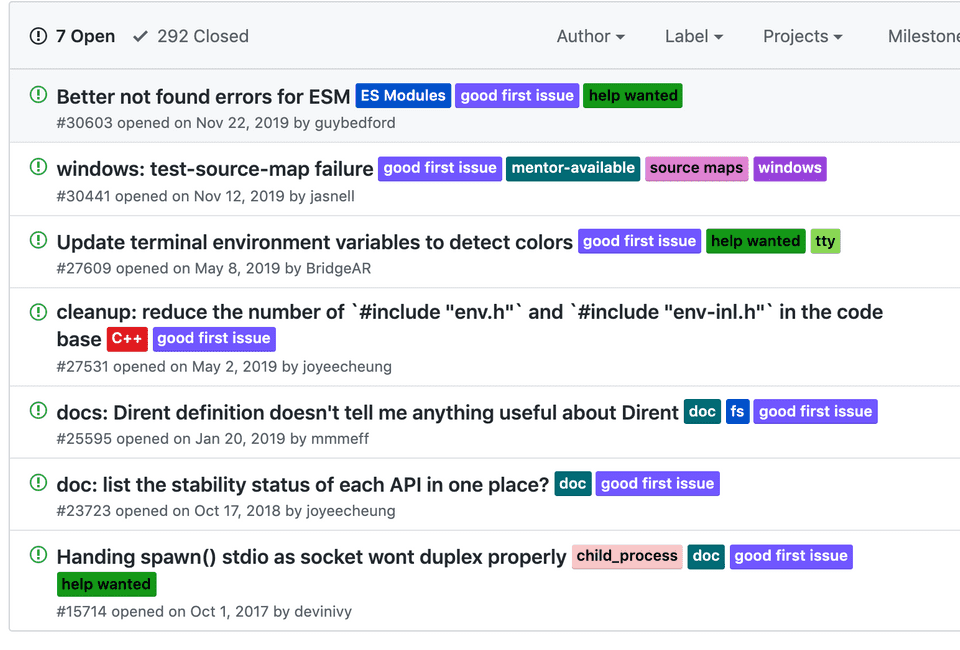

One of the biggest hurdles in contributing to open source is finding a project that you want to work on. A potential way of finding a project is to

think about the tools you use every day and think about how you would like to see it improved. That’s what I did with Better Pull Requests. Sites

like Up For Grabs and First Timers Only are fantastic resources for

discovering bugs and features people need help with. Many open source projects label issues as good-first-issue or beginner so be on the lookout

for those labels next time you’re browsing a project.

Takeaway

You don’t need to contribute to massive open source projects right away. Even if you do, your contributions don’t have to be huge; they can just be simple typo changes. Over time you’ll build up the momentum and confidence to contribute anywhere. The more reps you do the easier it’ll become.